It’s been just over a year since the passing of Gary Indiana, the American cultural critic and novelist who spent much of his life chronicling the moral exhaustion of late-century America. His work captured not only the shifting landscape of New York in the wake of the AIDS crisis, but also the broader decay and disillusionment creeping through the country at large. He’d long been on my list of writers to read and study, but, as often happens, I hadn’t gotten around to him until recently. When he died in October 2024 in his East Village apartment—and after reports that his entire personal library was lost in the L.A. wildfires the following January—it felt like a signal that if I was ever going to take a deep dive into his work, the time was now.

I began with this so-called “true crime” trilogy: Resentment, Three Month Fever, and Depraved Indifference. This reading project became an act of both immersion and inquiry. I wanted to understand how a writer could earn a reputation for being funny, biting, cruel, and clarifying, often in the same paragraph. As someone also drawn to fiction that operates within the uneasy space between real events, cultural “truths,” and gossip, I was curious how Indiana navigated those blurred lines. I then closed the sequence with Do Everything in the Dark, which lingers like an epilogue to the trilogy, cutting through the quiet absurdness of people trying to live inside a broken story.

Resentment: A Comedy (1997)

In this book, Indiana mirrors the Menendez brothers’ murder trial through a lens of fictionalization and spectacle. The tone he achieves is one of dark humor, detachment, and moral ambiguity. Splicing together lengthy trial excerpts that echo the real proceedings, he populates the narrative with a chorus of peripheral characters orbiting the courtroom’s chaos. The novel isn’t interested in proving the brothers’ guilt or innocence. It’s about exposing how everyone else (the reporters, jurors, and yes, even you the reader) becomes complicit in manufacturing narrative closure, no matter the cost.

Indiana’s depiction of the media circus is as biting as it is absurd: journalists bicker over front-row access, jockey for the best angles, and race to deliver the latest “exclusive.” Justice and show business collapse into one indistinguishable enterprise, a dynamic that feels no less relevant today than it did in the late 90’s.

The question at the heart of the book—what happens when truth becomes just another entertainment product?—connects vividly to my own work. As an avid consumer of true crime documentaries and podcasts, I’ve often grappled with my own complicity in the transformation of tragedy into content. These feelings helped inspire me to write my own novel, which attempts to inhabit that same void where moral outrage should be.

Indiana’s prose mirrors this moral fog. His long, looping sentences build both a sense of voyeuristic thrill and emotional fatigue. Half gossip, half sermon, we’re left with no answers and no moral high ground. We’re just simply exhausted at having witnessed too much. Irony becomes the only honest response.

***

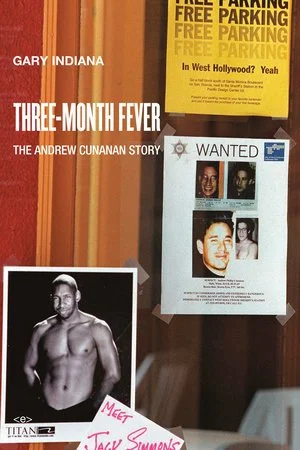

Three Month Fever: The Andrew Cunanan Story (1999)

If Resentment watched the circus from the bleachers, Three Month Fever steps inside the pit. Of the trilogy, it is the most intimate with its subject. Following the months leading up to Andrew Cunanan’s cross-country murder spree—which ended, most infamously, with the killing of Gianni Versace—Indiana constructs a fictionalized interiority that had never existed before.

In the wake of the murders, the media and nearly anyone who had ever said “hello” to Andrew, flooded the culture with wild theories that recast him as an isolated, greedy monster who seemed to materialize overnight. Many of these stories contradicted one another: he was said to be in a meth-induced psychosis, yet also bingeing on lavish meals and gaining so much weight as to become unrecognizable. The problem, as Indiana knew, was that the mythology didn’t add up. People addicted to stimulants don’t gorge themselves into obscurity. Something else was at work.

In truth, little was actually known about Cunanan’s adult life, and he was, by nature, an unreliable narrator. He was a different person to everyone he met. Not because he was some cold, calculating sociopath, but because he was a gay man, newly unmoored from a conservative upbringing, chasing validation, beauty, and belonging through acts of self-invention. It’s not an unfamiliar impulse. Many of us do the same today, performing versions of ourselves across social media, hoping to impress or be affirmed.

Here, Indiana’s study becomes one of performance as identity. He isn’t writing about Andrew’s pathology so much as the cultural machinery that rewards self-delusion. His critique feels as biting toward the image-obsessed 1990s as it does in our present moment.

The prose itself is hypnotic, circling. You can feel the walls tightening as Andrew spirals further into his own mythology, grasping at a truth about himself that keeps slipping through his fingers. It’s a chase—and the real horror is that these impulses to be seen, loved, and remembered are universal. Andrew isn’t a monster by exception. Indiana’s blend of fact, rumor, and fabrication isn’t merely stylistic; it’s the only truthful way to write about a man who never had a single, stable self. In a culture where everyone wears a mask, “truth” becomes just another performance.

***

Depraved Indifference (2002)

The final book in the trilogy plunges into a hollow, unsentimental, and ruthlessly cynical territory. Here, Indiana follows Evangeline and Devin Slote, a mother-son duo inspired by real-life con artists whose crimes unfolded over years, each scheme more brazen than the last. Evangeline becomes a near-allegorical figure: the embodiment of an American myth built on self-invention, deception, and the belief that survival alone can be mistaken for transcendence.

Where the first two books offer moments of interiority, glimpses into the emotional architecture of their subjects, Depraved Indifference looks outward, toward something much larger. Indiana reframes corruption not as deviance but as a national pastime. The truth, which Evangeline understands instinctively, is that everyone is running a con; some simply do it better than others.

Beneath the satire lies an awful familiar logic: the fear of degradation drives people to degrade others first. Evangeline’s cruelty isn’t inhuman—it’s painfully recognizable within a culture that rewards extraction over empathy. The endless grifts, the social climbing, the frantic relocations, and the manic, propulsive pacing of Indiana’s prose all mirror the psychological burnout of a nation addicted to reinvention.

If Resentment charted spectacle, and Three Month Fever dissected desire, Depraved Indifference completes Indiana’s triptych of American pathology. It reveals how a ruse becomes most effective in a society structured around plunder, where wealth is extracted, bodies are expendable, and the line between survival and predation dissolves entirely.

***

Do Everything in the Dark (2003)

Although Do Everything in the Dark sits outside the trilogy, and doesn’t dwell on true crime, its tonal shift into melancholy and existential drift makes it feel like a postscript. The cruelty of the earlier novels cools here, replaced by a weary resignation.

The book follows an ensemble of lonely characters moving through New York’s fading optimism, each trying to keep themselves busy, to stave off the sense that the world has already ended. What emerges is the lived texture of America’s slow-motion collapse. Not an apocalypse, but a drift—a society running on habit long after its meaning has expired.

Indiana never states this outright; he reveals it through behavior. Through routines and neurotic distractions. Through the small gestures of care that persist even when no redemption is possible. These characters are no longer in their idealistic youth. Life has hit them with one tragedy after another, and now they search for anything that might pull them out of the rut. The longing is quiet, almost embarrassed, but pervasive.

There’s no grand lesson here. No catharsis. No salvation. And yet the simple act of continuing, of waking up, of trying again, takes on a strange, understated power. In a world that keeps collapsing, persistence becomes its own form of grace.

***

Reading Indiana in this sequence illuminated something I hadn’t expected: that writing about ugliness, deceit, or delusion isn’t inherently cynical. It can be an act of precision, of seeing clearly what most people would rather ignore. His moral universe is still deeply human. He refuses sentimentality because he refuses false comfort, trusting his readers enough to sit with the mess rather than smoothing it over.

I think that’s why his work has lodged itself so firmly in my mind as I continue with my artistic work. My impulse toward ambiguity and moral unease comes from a similar place: a desire to understand how people keep performing meaning inside decay, how they construct stories about themselves even as the world around them frays. There’s something oddly hopeful in that impulse, even if the hope is thin.

After finishing these books, I’m left not with answers but with a kind of sharpened attention, an awareness that clarity and contempt can coexist, that honesty doesn’t require optimism. What remains, after all the chaos, is the small dignity of trying—to write, to love, to live—even as the lights dim.

Stay in the loop—no spam, no fluff, just my latest reflections, direct to you.